The Relationship Between CSS and SEO: How to Optimize It

While CSS is often seen as just a design tool, it's a crucial factor that directly impacts SEO performance. Unnecessarily large and complex CSS files can lead to negative consequences in critical SEO areas such as site speed, crawlability, mobile-friendliness, and Core Web Vitals.

In this article, we'll examine the technical effects of CSS on SEO, discuss how effective style management contributes to search engine optimization, and cover best practices in detail. Let's start with a definition of CSS.

What is CSS (Cascading Style Sheets)?

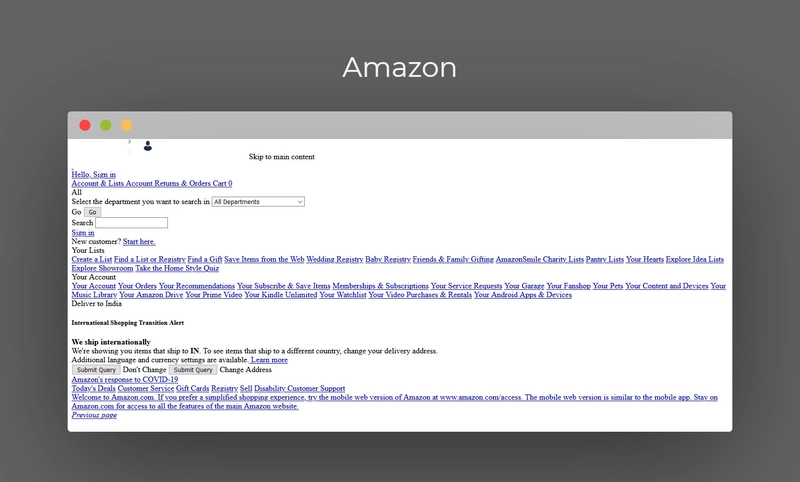

CSS is fundamentally a style sheet language that controls the visual design of web pages. It's layered on top of the structure and content provided by HTML to manage visual properties like colors, fonts, spacing, buttons, grid systems, and responsive layouts. Without CSS, websites would only display as simple, unformatted text and images. For example, the Amazon website without CSS would look like this:

From an SEO perspective, CSS isn't just an aesthetic tool; it's a technical component that shapes user experience and site performance. Given that Google prioritizes fast-loading websites that offer a better experience, we can conclude that CSS files must be optimized.

How Does CSS Affect SEO Performance?

1. Site Speed and Core Web Vitals

Site speed is a primary area that CSS impacts. If you've ever used a site speed measurement tool like PSI or GTmetrix, you've likely seen that the biggest savings come from optimizing JavaScript and CSS files. While these optimizations can be difficult to implement for a long-running, established system, they offer the most significant performance gains.

So, how exactly does CSS affect site speed?

CSS files are among the first resources that a browser reads and processes when loading a page. When a user opens a page, the browser downloads and processes the HTML and CSS together, and then renders the page visually. In this process, CSS optimization directly determines the site's speed.

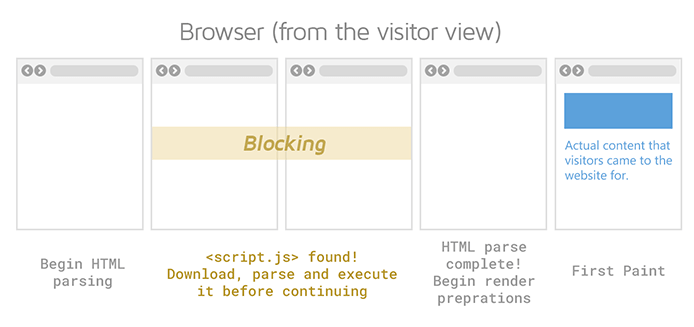

Render-Blocking Effect: CSS files are typically render-blocking, meaning the browser cannot display the visual content of the page until the CSS files have fully loaded. Unnecessarily large and uncombined CSS files can prolong this process, causing the page to load slowly. The example below shows how render-blocking JavaScript files can delay page loading. Similarly, CSS files can cause delays by preventing the page from rendering until the download is complete.

File Size and Load Time: CSS files that contain excessive code, are not minified, or include unused styles increase page load time. This directly and negatively impacts the Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) Core Web Vitals metric.

Using Critical CSS: Separating and preloading the CSS needed for the visible area of the page (above the fold) allows the site to provide a faster visual response to the user. Without this step, the user might see a blank screen or a broken layout upon their first interaction.

Impact on Mobile Performance: CSS bloat that might be tolerable on a desktop can lead to much more serious speed issues on mobile devices. For users with weak internet connections, unoptimized CSS files can result in users abandoning the site before it even loads.

2. Crawlability and Indexing

CSS doesn't just provide visual layout; it also helps search engines understand how a page looks. When Googlebot crawls a web page, it downloads the CSS files and interprets the style structure along with the content. This allows it to more accurately analyze how the page is presented to the user.

CSS Blocks: If your CSS files are blocked via robots.txt or a similar method, Google can't see the page's true appearance. In this case, the search engine will evaluate the page as incomplete or flawed. Specifically, blocking CSS access during mobile-friendliness tests can cause the site to be flagged as mobile-unfriendly.

Indexing Issues: Incorrectly loaded or unavailable CSS files can cause a page's content to be indexed incorrectly. For example, if menus or content are not displayed correctly, it can prevent Google from fully understanding the page's hierarchy. This can reduce the perceived importance of critical content in the eyes of the search engine.

Tired of reading?

You can also listen to this blog post as a podcast we created with Google NotebookLM on Spotify.

3. Mobile-Friendliness

Given Google's Mobile-First Indexing approach, mobile-friendliness is more crucial than ever for SEO performance. Websites that load quickly on mobile, are easy to read, and have simple interactions improve user satisfaction and support organic performance. In contrast, sites that ignore mobile-friendliness can face high bounce rates, low session durations, and organic traffic loss.

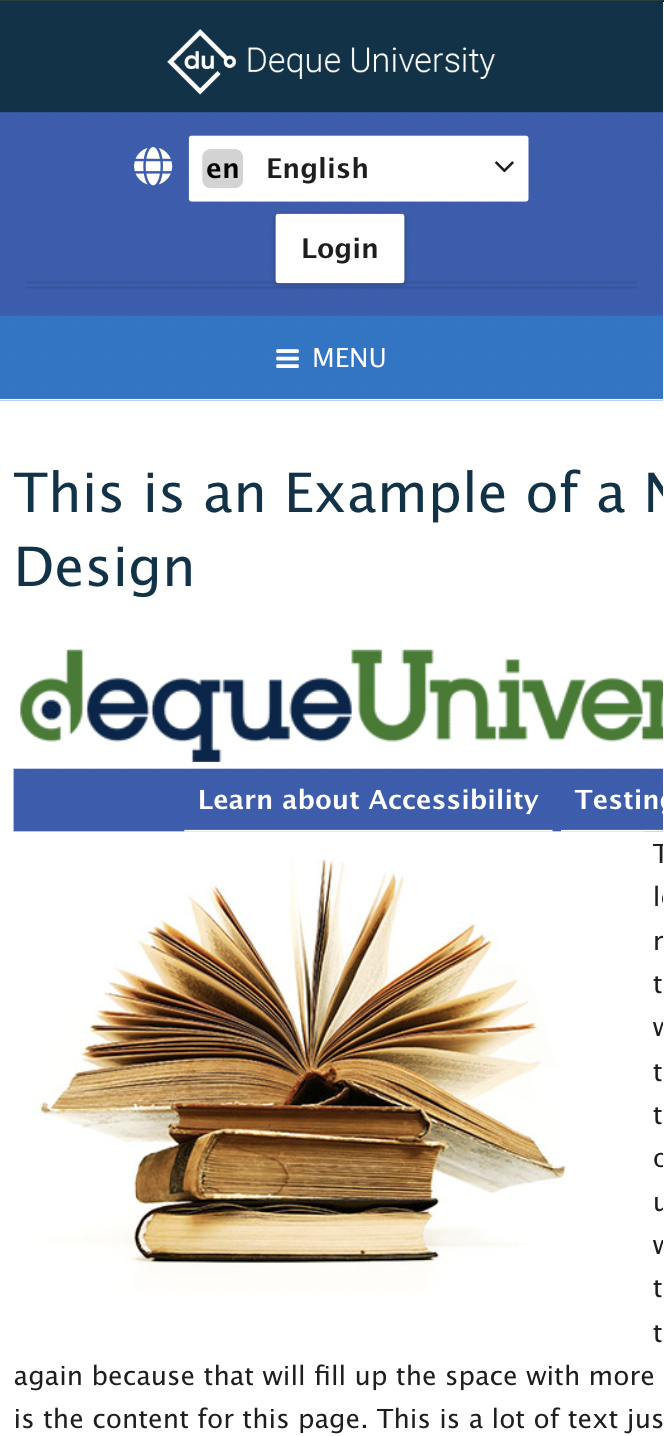

Responsive Design: CSS media queries allow for layouts that adapt to different screen sizes. Without this optimization, mobile users will encounter a cramped, hard-to-read layout designed for desktop. A non-responsive page looks like this:

Tap Targets: CSS can be used to control the size and spacing of buttons and links. Making these areas too small for mobile users degrades the user experience and can appear as an error in Google's mobile usability reports.

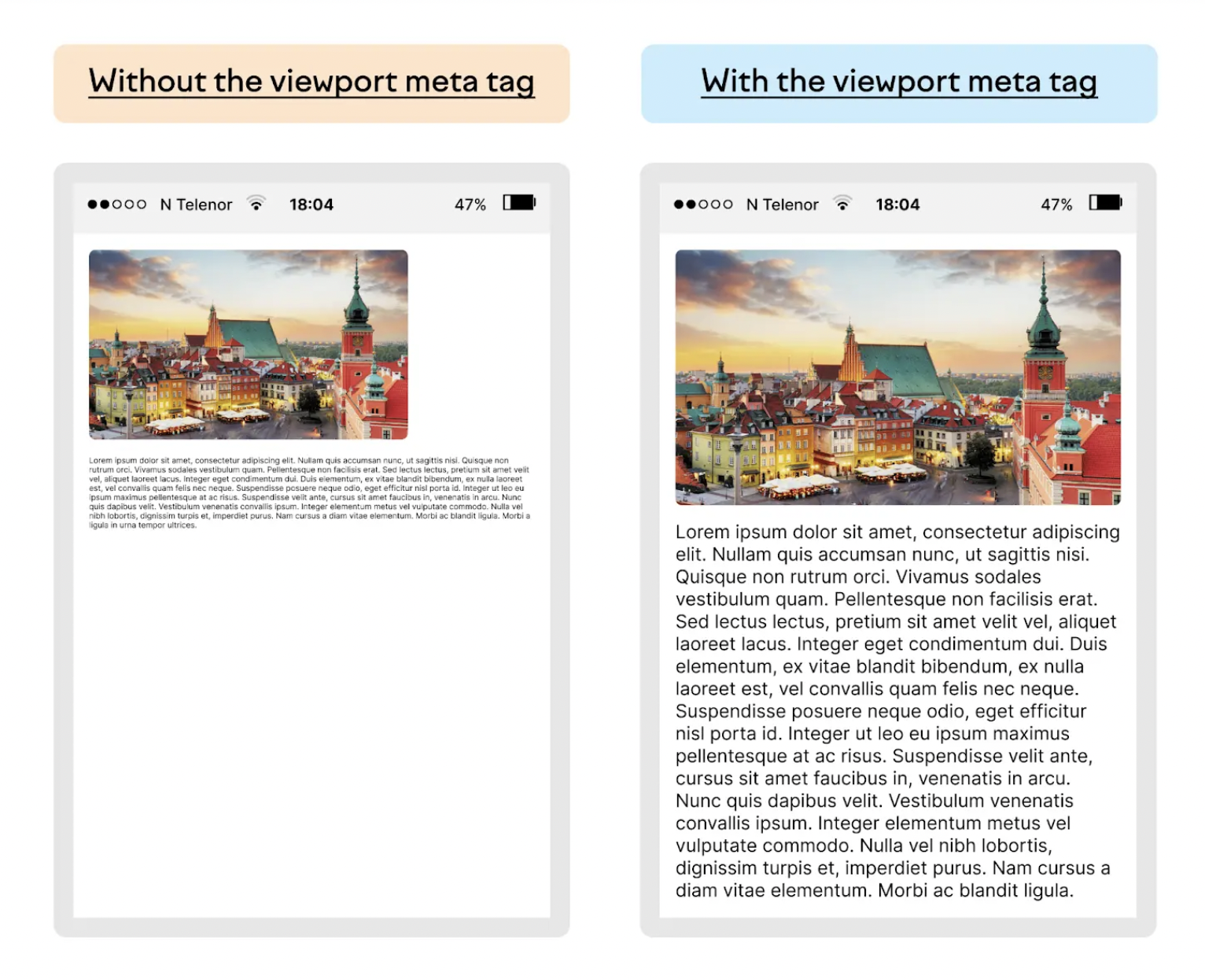

Viewport Settings: The <meta viewport> setting, used with CSS, ensures that a page is scaled correctly on mobile devices. Incorrect configuration can cause the page to appear too small or too large. You can find examples of pages with and without viewport settings below:

4. User Experience (UX)

User experience is another area where CSS has a significant impact, and it now plays a central role in Google's ranking signals. Providing a high-quality user experience across all devices is critical. How does CSS influence UX?

Readability: Font size, line height, paragraph layout, and color contrast are all determined by CSS. When these are not applied correctly, users can struggle to read the content and may quickly leave the page. For example, using a 16px font size and 150% line height makes text much easier to read than 12px font. Similarly, low-contrast combinations (like light gray text on a white background) reduce readability and negatively impact session duration.

Visual Hierarchy: Visually separating headings, subheadings, lists, and buttons helps users quickly understand the content flow. For example, using a large font size for h1, a medium size for h2, and a small size for h3 improves readability and clarifies content hierarchy. CSS-related factors like spacing between paragraphs and the alignment of visuals and text can also affect UX and SEO performance.

Interactions and Animations: Hover effects, transition animations, or micro-interactions can make a page feel more fluid. However, excessive animations or heavy CSS effects can slow the site down. It’s often beneficial for site speed to keep the design as simple as possible.

Usability: CSS can be used to style button colors, clickable areas, and error messages to improve user actions. For example, ensuring that buttons have a minimum tap target of 44x44px (in line with Google's mobile usability criteria) or highlighting form errors with a prominent CSS style can increase conversion rates.

How to Optimize CSS

There are many methods for CSS optimization, but implementing them isn't always easy. Below, you'll find a list of the most common CSS optimization techniques.

1. Minify Your CSS

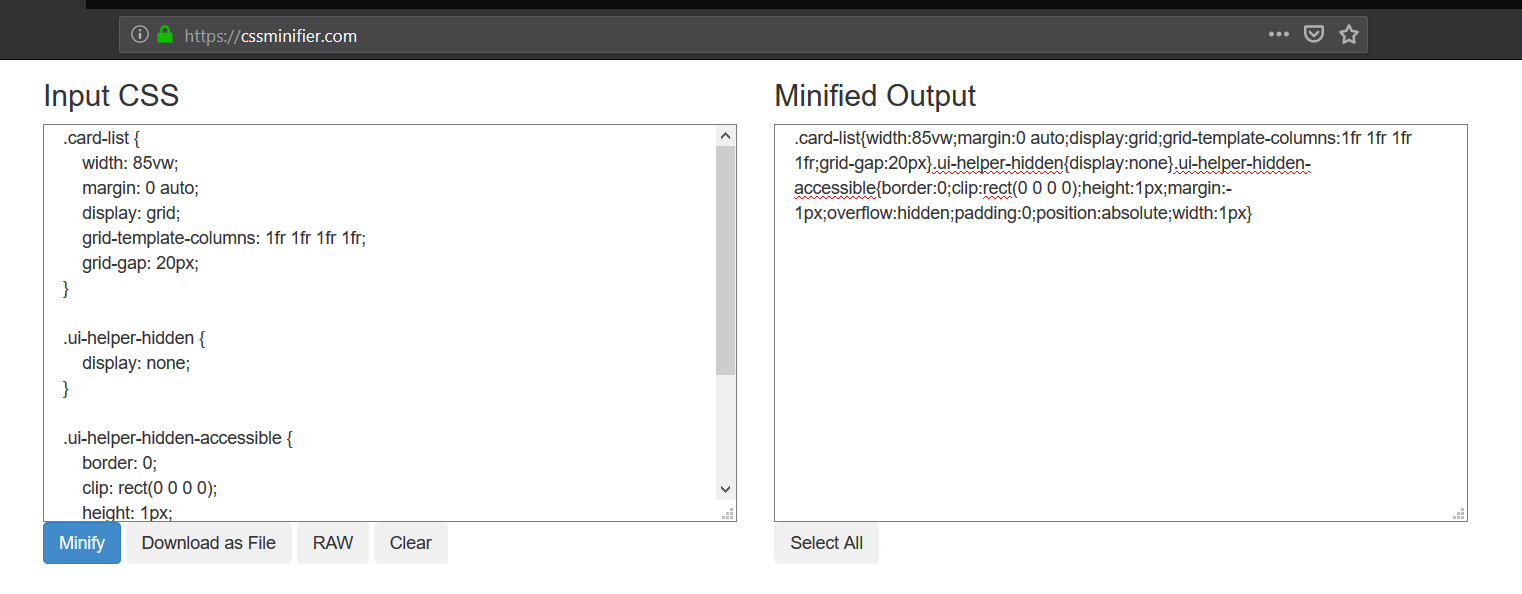

The first method is to minify your CSS files. The minification process removes unnecessary spaces, line breaks, comments, and other characters that are only for human readability. This reduces the file size and shortens the time it takes for a browser to download the file. Smaller files significantly improve the user experience, especially on mobile devices and with slow internet connections.

You can find an example of a minified CSS file below. You can also use free online tools to perform this process.

2. Remove Unused CSS Code

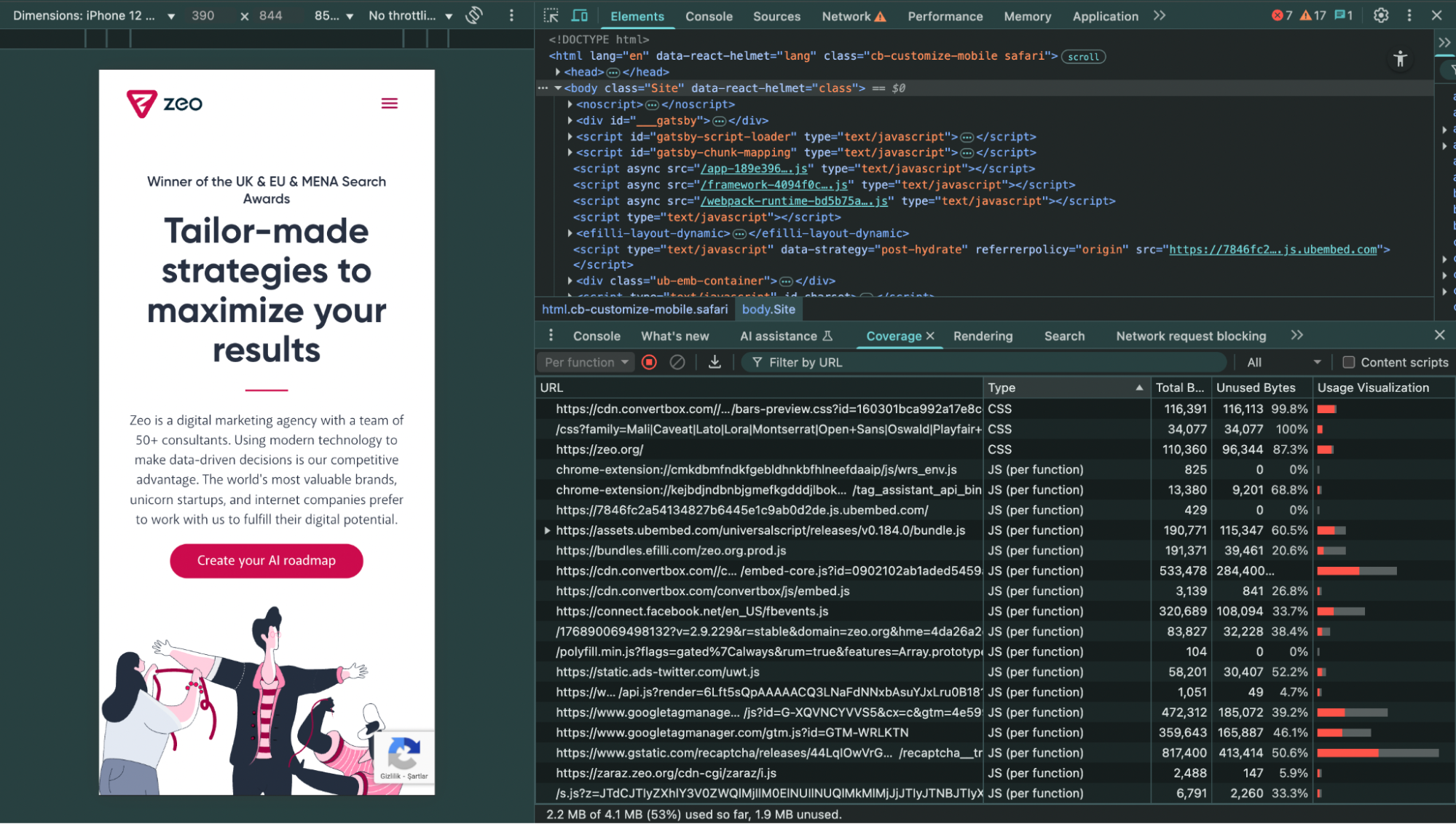

Unused CSS code directly affects page load time. Over time, unused CSS rules can accumulate due to design changes, plugin usage, or framework integrations. This excess code increases page load time and slows down the browser's rendering process. It is critically important for performance only to use the code that is needed.

You can use the Chrome DevTools Coverage tab to detect unused CSS files on a per-page basis. Before removing these files, I recommend making sure they are not used on other pages of your site.

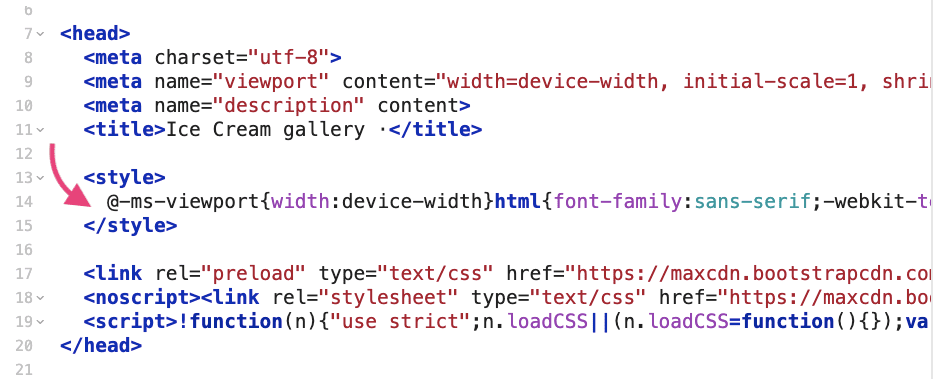

3. Implement Critical CSS

Critical CSS refers to the practice of isolating and prioritizing the styles needed for the initial, visible part of a page (above the fold). This method ensures that the above-the-fold content loads quickly while the rest of the page continues to load in the background. If not implemented, the browser cannot display the content on the screen until all CSS files are downloaded, which lengthens the page's load time. This has a negative effect on the Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) Core Web Vitals metric.

In the example below, you can see that the critical CSS is added to the top of the HTML.

4. Combine CSS Files

A large number of small CSS files can increase the number of HTTP requests a browser has to make, which creates a burden. Making a separate request for each file negatively impacts page load time, especially on mobile devices and with slow internet connections. Combining CSS files can be helpful for reducing the number of requests. A single, larger CSS file can be downloaded and processed more quickly by the browser.

However, a single, large CSS file is not always the best solution. If different pages have different CSS needs, it may be more efficient to keep critical styles separate from page-specific styles. The best approach is to consolidate commonly used CSS rules into a single file and load page-specific styles in separate files.

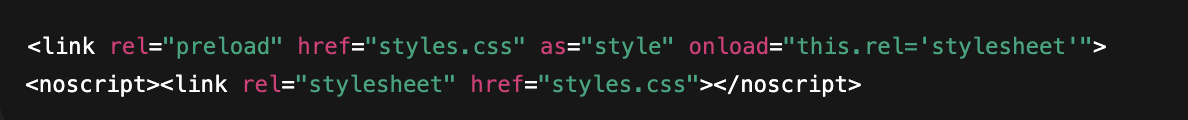

5. Defer Non-Critical CSS (Preload & Media Attribute)

By default, CSS files are render-blocking, meaning the browser cannot display the visual output of the page until they are loaded. You can use different methods to defer the loading of non-critical CSS files.

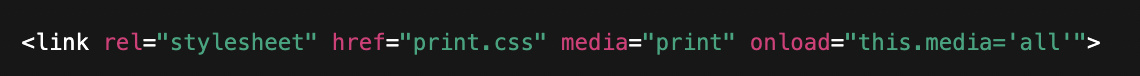

Preload + Onload Method: The <link rel="preload"> tag can be used to preload the CSS file. Then, the onload attribute ensures that the file is applied as a style. This way, the CSS loads without blocking the initial rendering of the page.

Using the Media Attribute: The CSS file is initially loaded with a different media value and then changed to all once the page is loaded. This technique allows you to defer non-critical CSS.

Use Cases:

- These methods are suitable for CSS files that are not visible in the above-the-fold area (e.g., footer, lower components).

- Styles that are not essential for the user's first view can be deferred.

These approaches improve First Contentful Paint (FCP) and Time to Interactive (TTI) metrics. However, you must be careful, as incorrect implementation can lead to a Flash of Unstyled Content (FOUC).

6. Use a CDN

A CDN (Content Delivery Network) is a system that distributes CSS files from servers in different geographic locations. When a user visits your site, their browser downloads the CSS file from the server closest to them. This shortens the file's load time and improves site performance.

Using a CDN is critically important for sites with a global audience. For example, a user in Turkey would pull the files from a server in Istanbul or Frankfurt, while a user in the US would download the same files from a server in New York or Los Angeles. This structure reduces latency and helps CSS files process faster.

7. Leverage Browser Caching

Browser caching saves CSS files on the user's device, which allows the page to load much faster on subsequent visits. During the first visit, the CSS file is downloaded from the server and stored in the browser's cache. When the user revisits the site, the browser uses the cached copy instead of downloading the same file again.

This method can significantly boost performance, especially for large-scale sites. For example, on an e-commerce site, the same CSS files are not downloaded repeatedly as a user navigates between different product pages; the browser loads them from the cache. This not only increases page speed but also reduces the number of requests to the server.

You can use HTTP headers (e.g., Cache-Control, Expires) to define long-term caching for CSS files. This way, the browser will use the cached version as long as the files are not updated. This approach has a direct positive effect on the First Contentful Paint (FCP) Core Web Vitals metric.

8. Use CSS Sprites

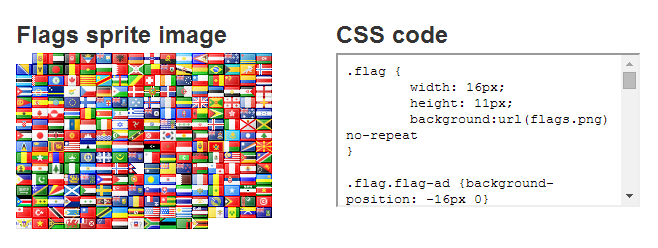

The CSS sprite technique involves combining multiple small images (like icons, buttons, or background images) into a single, larger image file. With this method, the browser downloads only one image, and the relevant parts are displayed using CSS coordinates. Using sprites, especially for menu icons, social media icons, or small UI elements, can be beneficial for site speed. The example below shows how all the flags are combined into a single image, and a specific area is defined for each flag using CSS.

The impact of CSS on SEO is too great to ignore. Unoptimized CSS files can lead to performance loss in many critical areas, from site speed and Core Web Vitals to mobile-friendliness and user experience. Therefore, CSS files should not be viewed as merely visual design tools but as elements that must be optimized for SEO.